Ancien Régime

1400s–1789 sociopolitical system of the Kingdom of France / From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dear Wikiwand AI, let's keep it short by simply answering these key questions:

Can you list the top facts and stats about Ancien Régime?

Summarize this article for a 10 years old

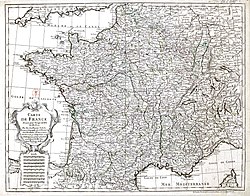

The Ancien Régime (/ˌɒ̃sjæ̃ reɪˈʒiːm/; French: [ɑ̃sjɛ̃ ʁeʒim]; lit. 'old rule'),[lower-alpha 1] also known as the Old Regime, was the political and social system of the Kingdom of France from the Late Middle Ages (c. 1500) until 1789 and the French Revolution,[1] which abolished the feudal system of the French nobility (1790)[2] and hereditary monarchy (1792).[3] The Valois Dynasty ruled during the Ancien Régime up until 1589 and was subsequently replaced by the Bourbon dynasty. The term is occasionally used to refer to the similar feudal systems of the time elsewhere in Europe such as that of Switzerland.[4]

|

| Ancien Régime |

|---|

| Structure |

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancien Régime

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in France |

|---|

|

|

Intellectuals |

|

Works

|

The administrative and social structures of the Ancien Régime in France evolved across years of state-building, legislative acts (like the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts), and internal conflicts. The Valois dynasty's attempts at reform and at re-establishing control over the scattered political centres of the country were hindered by the Wars of Religion from 1562 to 1598.[5] During the Bourbon dynasty, much of the reigns of Henry IV (r. 1589–1610) and Louis XIII (r. 1610–1643) and the early years of Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715) focused on administrative centralization. Despite the notion of "absolute monarchy" (typified by the king's right to issue orders through lettres de cachet) and efforts to create a centralized state, Ancien Régime France remained a country of systemic irregularities: administrative, legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions and prerogatives frequently overlapped, while the French nobility struggled to maintain their rights in the matters of local government and justice, and powerful internal conflicts (such as The Fronde) protested against this centralization.

The drive for centralization related directly to questions of royal finances and the ability to wage war. The internal conflicts and dynastic crises of the 16th and the 17th centuries between Catholics and Protestants, the Habsburgs' internal family conflict, and the territorial expansion of France in the 17th century all demanded great sums, which needed to be raised by taxes, such as the land tax (taille) and the tax on salt (gabelle), and by contributions of men and service from the nobility.

One key to the centralization was the replacing of personal patronage systems, which had been organised around the king and other nobles, by institutional systems that were constructed around the state.[6] The appointments of intendants, representatives of royal power in the provinces, greatly undermined the local control by regional nobles. The same was true of the greater reliance that was shown by the royal court on the noblesse de robe as judges and royal counselors. The creation of regional parlements had the same initial goal of facilitating the introduction of royal power into the newly assimilated territories, but as the parlements gained in self-assurance, they started to become sources of disunity.